Storage-attached indexing (SAI) concepts

Storage-Attached Indexing (SAI) is a highly-scalable, globally-distributed index for Cassandra databases.

The main advantage of SAI over existing indexes for Apache Cassandra are:

-

enables vector search for AI applications

-

shares common index data across multiple indexes on same table

-

alleviates write-time scalability issues

-

significantly reduced disk usage

-

great numeric range performance

-

zero copy streaming of indexes

In fact, SAI provides the most indexing functionality available for Apache Cassandra. SAI adds column-level indexes to any CQL table column of almost any CQL data type.

SAI enables queries that filter based on:

-

vector embeddings

-

AND/OR logic for numeric and text types

-

IN logic (use an array of values) for numeric and text types

-

numeric range

-

non-variable length numeric types

-

text type equality

-

CONTAINs logic (for collections)

-

tokenized data

-

row-aware query path

-

case sensitivity (optional)

-

unicode normalization (optional)

Advantages

Defining one or more SAI indexes based on any column in a database table subsequently gives you the ability to run performant queries that specify the indexed column. Especially compared to relational databases and complex indexing schemes, SAI makes you more efficient by accelerating your path to developing apps.

SAI is deeply integrated with the storage engine of Cassandra. The SAI functionality indexes the in-memory memtables and the on-disk SSTables as they are written, and resolves the differences between those indexes at read time. Consequently, the design of SAI has very little operational complexity on top of the core database. From snapshot creation, to schema management, to data expiration, SAI integrates tightly with the capabilities and mechanisms that the core database already provides.

SAI is also fully compatible with zero-copy streaming (ZCS). Thus, when you bootstrap or decommission nodes in a cluster, the indexes are fully streamed with the SSTables and not serialized or rebuilt on the receiving node’s end.

At its core, SAI is a filtering engine, and simplifies data modeling and client applications that would otherwise rely heavily on maintaining multiple query-specific tables.

Performance

SAI outperforms any other indexing method available for Apache Cassandra.

SAI provides more functionality than secondary indexing (2i), using a fraction of the disk space, and reducing the total cost of ownership (TCO) for disk, infrastructure, and operations. For read path performance, SAI performs at least as well as the other indexing methods for throughput and latency.

SAI write path and read path

SAI is deeply integrated with the storage engine of the underlying database. SAI does not abstractly index tables. Instead, SAI indexes Memtables and Sorted String Tables (SSTables) as they are written, resolving the differences between those indexes at read time. Each Memtable is an in-memory data structure that is specific to a particular database table. A Memtable resembles a write-back cache. Each SSTable is an immutable data file to which the database writes Memtables periodically. SSTables are stored on disk sequentially and maintained for each database table.

This topic discusses the details of the SAI read and write paths, examining the SAI indexing lifecycle.

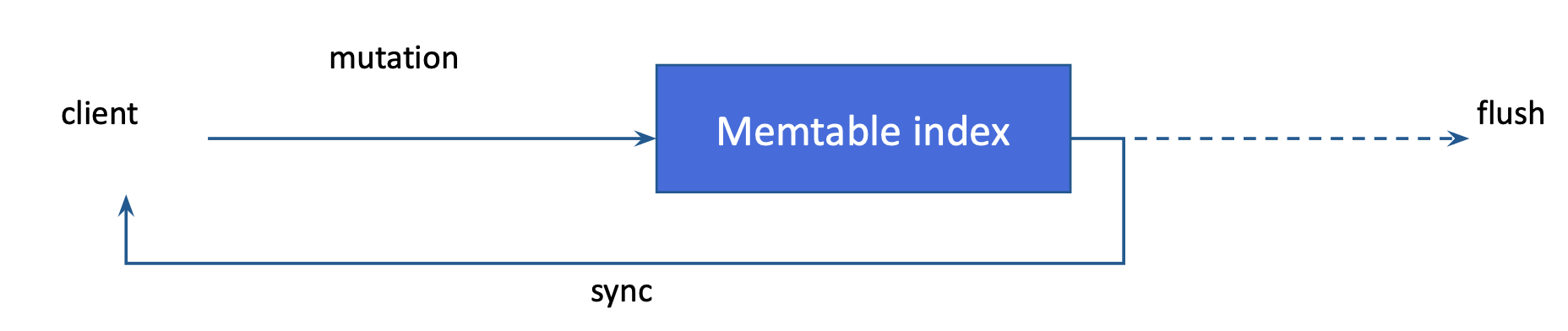

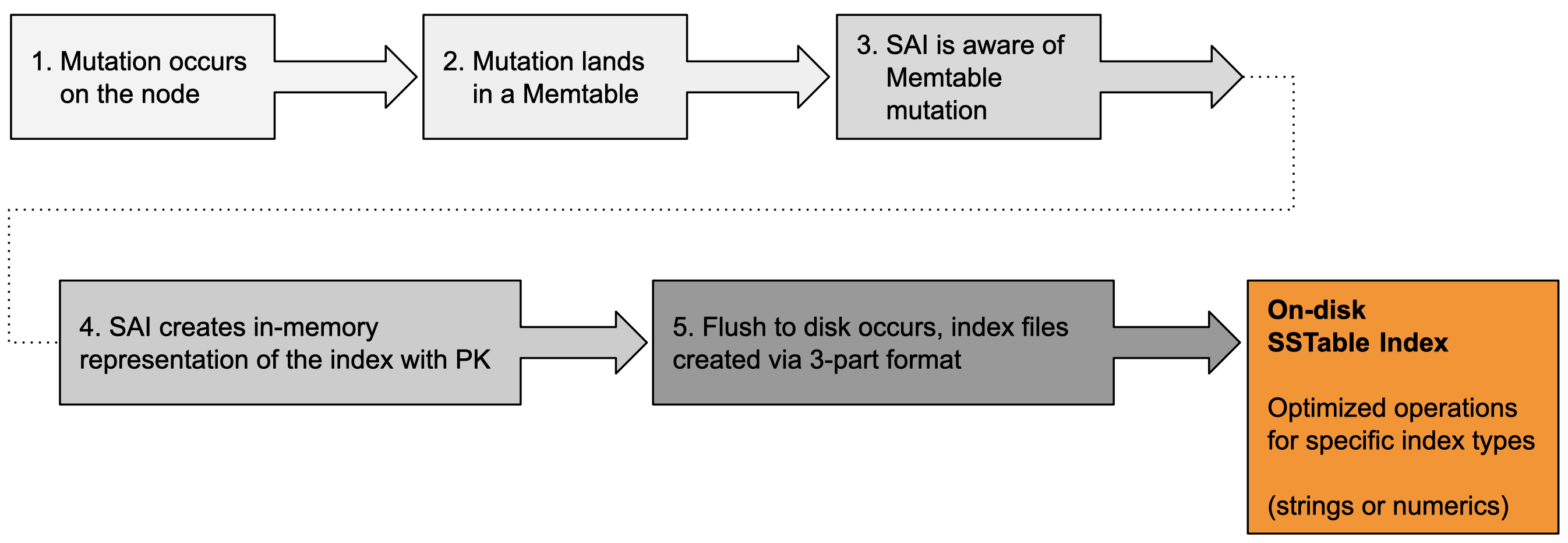

SAI write path

An SAI index can be created either before any data is written to a CQL table, or after data has been written. As a refresher, data written to a CQL table will first be written to a Memtable, and then to an SSTable once the data is flushed from the Memtable. After an SAI index is created, SAI is notified of all mutations against the current Memtable. Like any other data, SAI updates the indexes for inserts and updates, which Apache Cassandra treats in exactly the same way. SAI also supports partition deletions, range tombstones, and row removals. If a delete operation is executed in a query, SAI handles index changes in a post-filtering step. As a result, SAI imposes no special penalties when indexing frequently deleted columns.

If an insert or update contains valid content for the indexed column, the content is added to a Memtable index, and the primary key of the updated row is associated with the indexed value. SAI calculates an estimate of the incremental heap consumption of the new entry. This estimate counts against the heap usage of the underlying Memtable. This feature also means that as more columns are indexed on a table, the Memtable flush rate will increase, and the size of flushed SSTables will decrease. The number of total writes and the estimated heap usage of all live Memtable indexes are exposed as metrics. See SAI metrics.

Memtable flush

SAI flushes Memtable index contents directly to disk when the flush threshold is reached, rather than creating an additional in-memory representation. This is possible because Memtable indexes are sorted by term/value and then by primary key. When the flush occurs, SAI writes a new SSTable index for each indexed column, as the SSTable is being written.

The flush operation is a two-phase process. In the first phase, rows are written to the new SSTable. For each row, a row ID is generated and three index components are created. The components are:

-

On-disk mappings of row IDs to their corresponding token values — SAI supports the Murmur3Partitioner

-

SSTable partition offsets

-

A temporary mapping of primary keys to their row IDs, which is used in a subsequent phase

The contents of the first and second component files are compressed arrays whose ordinals correspond to row IDs.

In the second phase, after all rows are written to the new SSTable and the shared SSTable-level index components have been completed, SAI begins its indexing work on each indexed column. Specifically in the second phase, SAI iterates over the Memtable index to produce pairs of terms and their token-sorted row IDs. This iterator translates primary keys to row IDs using the temporary mapping structure built in the first phase. The terms iterator (with postings) is then passed to separate writing components based on whether each indexed element is for a string or numeric column.

In the string case, the SAI index writer iterates over each term, first writing its postings to disk, and then recording the offset of those postings in the postings file as the payload of a new entry (for the term itself) in an on-disk, byte-ordered trie. In the numeric case, SAI separates the writing of a numeric index into two steps:

The terms are passed to a balanced kd-tree writer, which writes the kd-tree to disk. As the leaf blocks of the tree are written, their postings are recorded temporarily in memory. Those temporary postings are then used to build postings on-disk, at the leaves, and at various levels of the index nodes.

When a column index flush completes, a special empty marker file is flagged to indicate success. This procedure is used on startup and incremental rebuild operations to differentiate case where:

-

SSTable index files are missing for a column.

-

There is no indexable data — such as when an SSTable only contains tombstones. (A tombstone is a marker in a row that indicates a column was deleted. During compaction, marked columns are deleted.)

SAI then increments a counter on the number of Memtable indexes flushed for the column, and adds to a histogram the number of cells flushed per second.

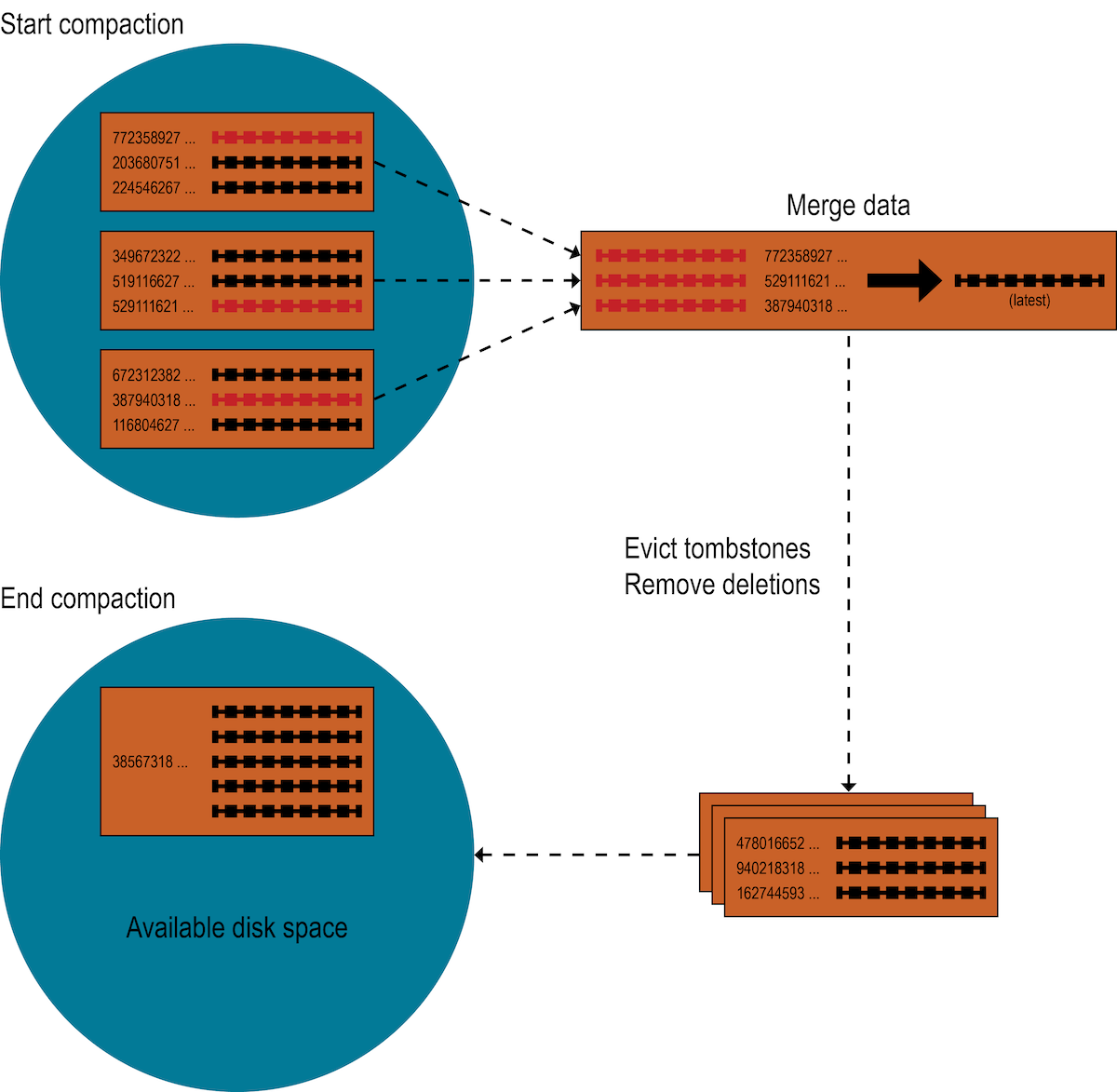

When compaction is triggered

Recall that Apache Cassandra uses compaction to merge SSTables. Compaction collects all versions of each unique row and assembles one complete row, using the most up-to-date version (by timestamp) of each of the row’s columns from the SSTables. The merge process is performant, because rows are sorted by partition key within each SSTable, and the merge process does not use random I/O. The new versions of each row is written to a new SSTable. The old versions, along with any rows that are ready for deletion, are left in the old SSTables, and are deleted when any pending reads are completed.

For SAI, when compaction is triggered, each index group creates an SSTable Flush Observer to coordinate the process of writing all attached column indexes from the newly compacted data in their respective SSTable writer instances. Unlike Memtable flush (where indexed terms are already sorted), when iterating merged data during compaction, SAI buffers indexed values and their row ids, which are added in token order.

To avoid issues such as exhausting available heap resources, SAI uses an accumulated segment buffer, which is flushed to disk synchronously by using a proprietary calculation. Then each segment records a segment row ID offset and only stores the segment row ID (SSTable row ID minus segment row ID offset). SAI flushes segments into the same file synchronously to avoid the cost of rewriting all segments and to reduce the cost of partition-restricted queries and paging range queries, as it reduces the search space.

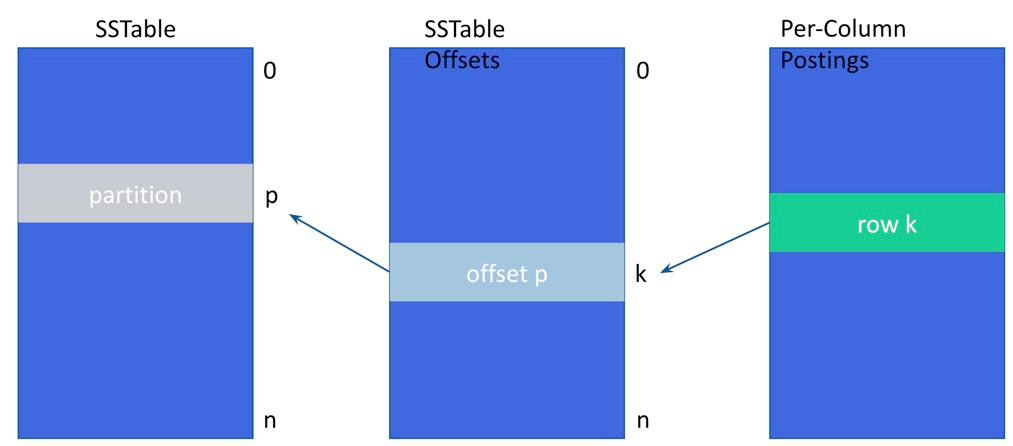

The on-disk layout from the per-column indexed posting, to the SSTable offset, to the SSTable partition:

The actual segment flushing process is very similar to a Memtable flush. However, buffered terms are sorted before they can be written with their postings to their respective type-specific on-disk structures. At the end of compaction for a given index, a special empty marker file is flagged to indicate success, and the number of segments is recorded in SAI metrics. See Global indexing metrics.

When the entire compaction task finishes, SAI receives an SSTable List Changed Notification that contains the SSTables added and removed during the transaction. SSTable Context Manager and Index View Manager are responsible for replacing old SSTable indexes with new ones atomically. At this point, new SSTable indexes are available for queries.

SAI read path

This section explains how index queries are processed by the SAI coordinator and executed by replicas.

Unlike legacy secondary indexes, where at most one column index will be used per query, SAI implements a Query Plan that makes it possible to use all available column indexes in a single query.

The overall flow of a SAI read operation is as follows:

Index selection and Coordinator processing

When presented with a query, the first action the SAI Coordinator performs, to take advantage of one or more indexes, is to identify the most selective index. That most selective index is the index that will most aggressively narrow the filtering space and the number of ultimate results by returning the lowest value from an estimated results row calculation. If multiple SAI indexes are present (that is, where each SAI index is based on a different column, but the query involves more than one column), it does not matter which SAI index is selected first.

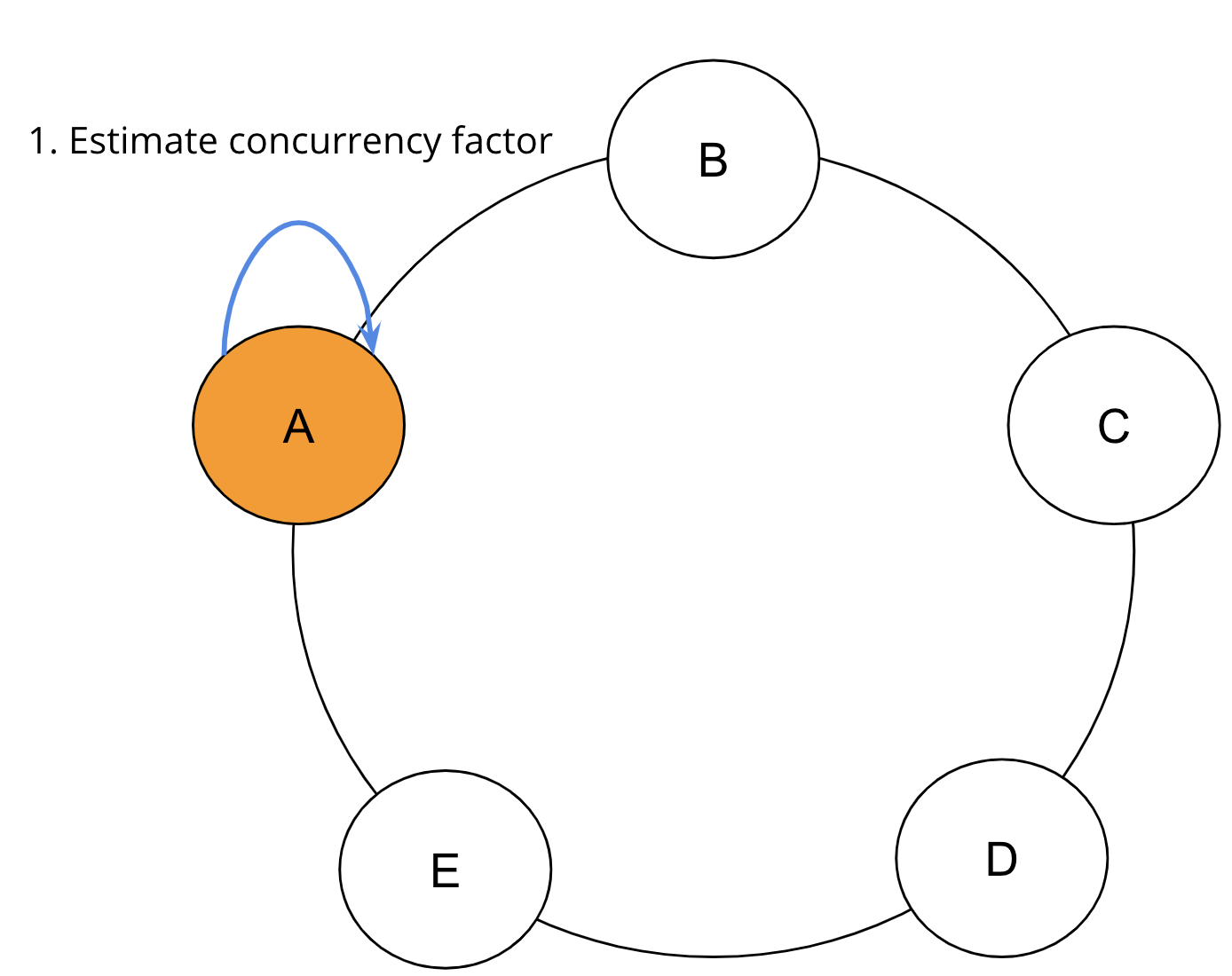

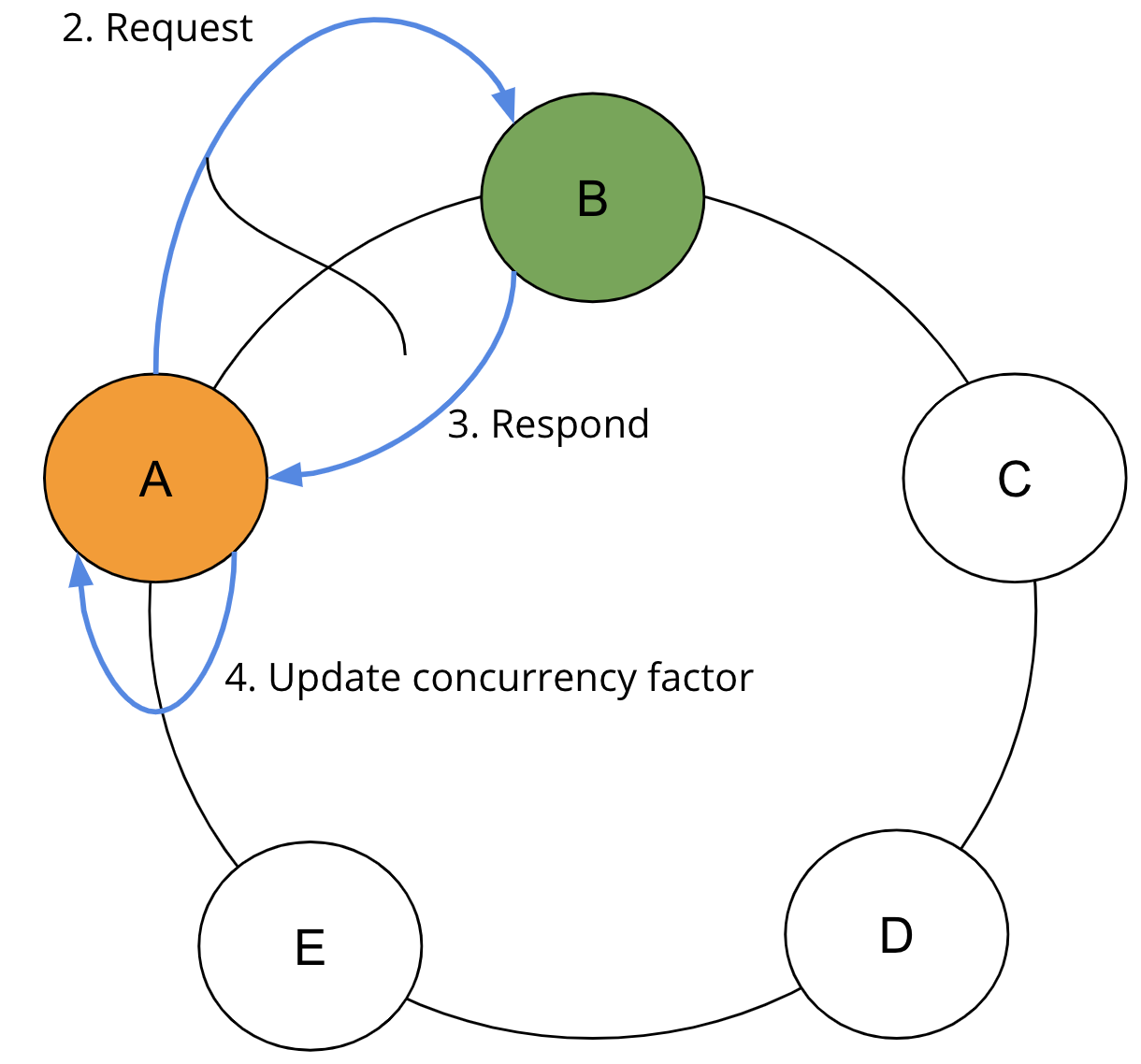

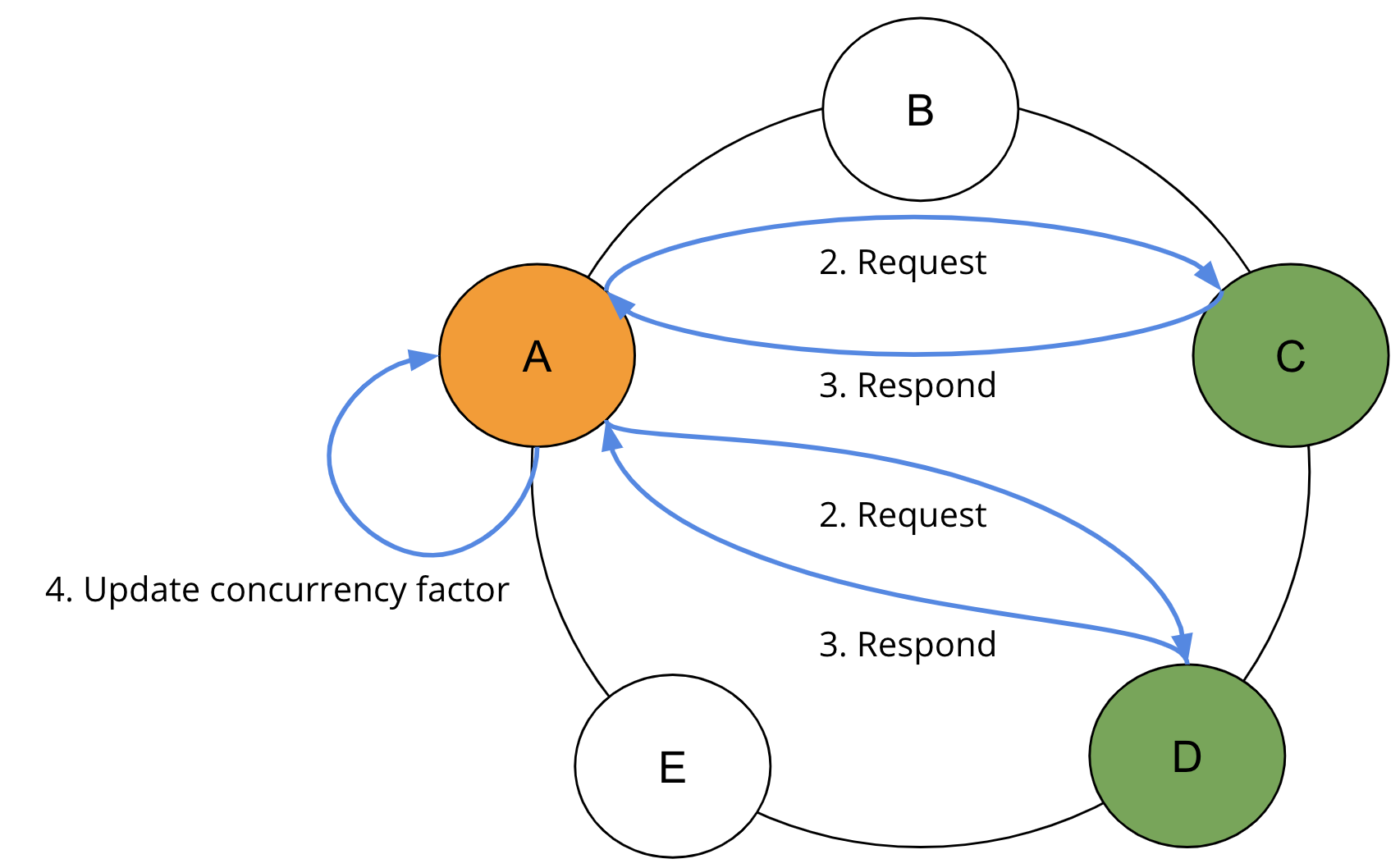

Once the best index for the read operation is selected, the index is embedded with the read command, which enters the distributed range read apparatus. A distributed range read queries the Apache Cassandra cluster in one or more rounds in token order. The SAI Coordinator estimates the concurrency factor, the number of rows per range based on local data and the query limit to determine the number of ranges to contact. For each round, a concurrency factor determines how many replicas will be queried in parallel.

Before the first round commences, SAI estimates the initial concurrency factor via a proprietary calculation, shown here as Step 1.

Once the initial concurrency factor established, the range read begins.

In Step 2, the SAI Coordinator sends requests to the required ranges in parallel based on the Concurrency factor. In Step 3, the SAI Coordinator waits for the responses from the requested replicas. And in Step 4, SAI Coordinator collects the results and recomputes the concurrency factor based on returned rows and query limit.

At the completion of each round, if the limit has not been reached, the concurrency factor is adjusted to take into account the shape of the results already read. If no results are returned from the first round, the concurrency factor is immediately increased to the minimum calculation of remaining token ranges and the maximum calculation of the concurrency factor. If results are returned, the concurrency factor is updated. SAI repeats steps 2, 3, and 4 until the query limit is satisfied.

To avoid querying replicas with failed indexes, each node propagates its own local index status to peers via gossip. At the coordinator, read requests will filter replicas that contain non-queryable indexes used in the request. In most cases, the second round of replica queries should return all the necessary results. Further rounds may be necessary if the distribution of results around the replicas is extremely imbalanced.

A closer look: replica query planning and view acquisition

Once a replica receives a token range read request from the SAI Coordinator, the local index query begins. SAI implements an index searcher interface via a Query Plan that makes it possible to access all available SAI column indexes in a single query.

The Query Plan performs an analysis of the expressions passed to it via the read command. SAI determines which indexes should be used to satisfy the query clauses on the given columns. Once column expressions are paired with indexes, a view of the active SSTable indexes for each column index is acquired by a Query Controller. In order to avoid compaction removing index files used by in-flight queries, before reading any index files, the Query Controller tries to acquire references to the SSTables for index files that intersect with the query’s token range, and releases them when the read request completes.

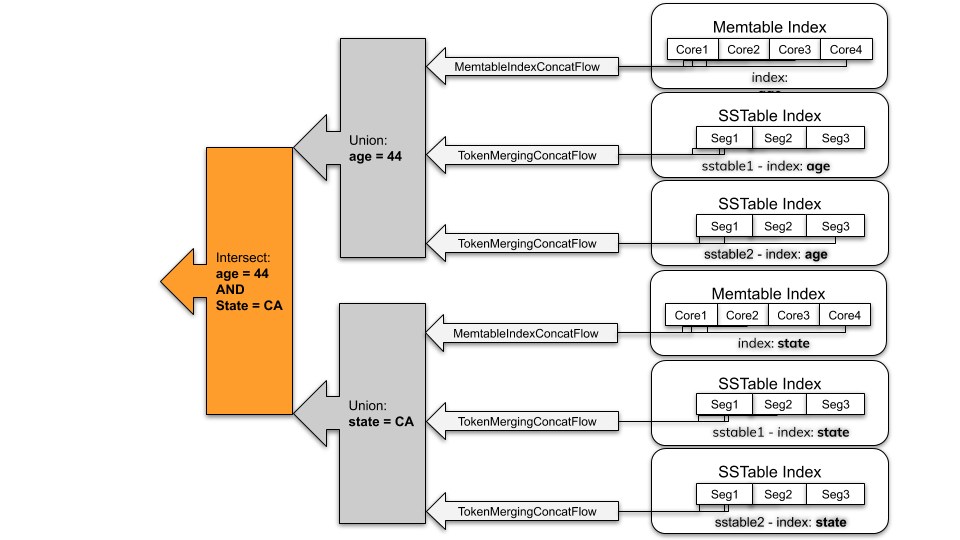

At this point, a Token Flow is created to stream matches from each column index. Those flows, along with the Boolean logic that determines how they are merged, is wrapped up in an Operation, which is returned to the Query Plan component.

Role of the SAI Token Flow framework

The SAI query engine revolves around a Token Flow framework that defines how SAI asynchronously iterates over, skips into, and merges streams of matching partitions from both individual SSTable indexes and entire column indexes. SAI uses a token to describe a container for partition matches within a Cassandra ring token.

Iteration is the simplest of the three operations. Specifically, the iteration of postings involves sequential disk access — via the chunk cache — to row IDs, which are used to lookup ring token and partition key offset information.

Token skipping is used to skip unmatched tokens when continuing from the previous paging boundary, or when a larger token is found during token intersection.

Match streaming and post filtering example

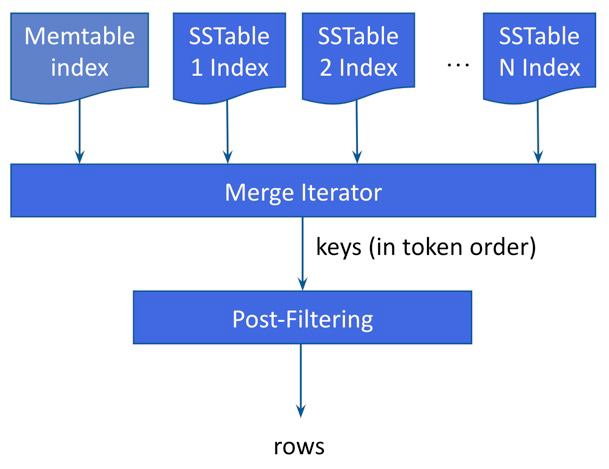

Consider an example with an individual column index (such as age = 44), the flow produced is the union of all Memtable indexes and all SSTable indexes.

-

SAI iterates over each Memtable index "lazily" (that is, one at a time) in token order through its individual token range-partitioned instances. This feature reduces the overhead that would occur otherwise from unnecessary searches of data toward the end of the ring.

-

On-disk index: SAI returns the union of all matching SSTable index. Within one SSTable index, there can be multiple segments because of the memory limit during compaction. Similar to the Memtable index, SAI lazily searches segments in token sorted order.

When there are multiple indexed expressions in the query (such as WHERE age=44 AND state='CA') connected with AND query operator, the results of indexed expressions are intersected, which returns partition keys that match all indexed expressions.

After the index search, SAI exposes a flow of partition keys. For every single partition key, SAI executes a single partition read operation, which returns the rows in the given partition. As rows are materialized, SAI uses a filter tree to apply another round of filtering. SAI performs this subsequent filtering step to address the following:

-

Partition granularity: SAI keeps track of partition offsets. In the case of a wide partition schema, not all rows in the partition will match the index expressions.

-

Tombstones: SAI does not index tombstones. It’s possible that an indexed row has been shadowed by newly added tombstones.

-

Non-indexed expressions: Operations may include non-index expressions for which there are no index structures.