Evaluating and Refining Data Models

Once you’ve created a physical model, there are some steps you’ll want to take to evaluate and refine table designs to help ensure optimal performance.

Calculating Partition Size

The first thing that you want to look for is whether your tables will have partitions that will be overly large, or to put it another way, too wide. Partition size is measured by the number of cells (values) that are stored in the partition. Cassandra’s hard limit is 2 billion cells per partition, but you’ll likely run into performance issues before reaching that limit.

In order to calculate the size of partitions, use the following formula:

The number of values (or cells) in the partition (Nv) is equal to the number of static columns (Ns) plus the product of the number of rows (Nr) and the number of of values per row. The number of values per row is defined as the number of columns (Nc) minus the number of primary key columns (Npk) and static columns (Ns).

The number of columns tends to be relatively static, although it is possible to alter tables at runtime. For this reason, a primary driver of partition size is the number of rows in the partition. This is a key factor that you must consider in determining whether a partition has the potential to get too large. Two billion values sounds like a lot, but in a sensor system where tens or hundreds of values are measured every millisecond, the number of values starts to add up pretty fast.

Let’s take a look at one of the tables to analyze the partition size.

Because it has a wide partition design with one partition per hotel,

look at the available_rooms_by_hotel_date table. The table has four

columns total (Nc = 4), including three primary key columns (Npk =

3) and no static columns (Ns = 0). Plugging these values into the

formula, the result is:

Therefore the number of values for this table is equal to the number of rows. You still need to determine a number of rows. To do this, make estimates based on the application design. The table is storing a record for each room, in each of hotel, for every night. Let’s assume the system will be used to store two years of inventory at a time, and there are 5,000 hotels in the system, with an average of 100 rooms in each hotel.

Since there is a partition for each hotel, the estimated number of rows per partition is as follows:

This relatively small number of rows per partition is not going to get you in too much trouble, but if you start storing more dates of inventory, or don’t manage the size of the inventory well using TTL, you could start having issues. You still might want to look at breaking up this large partition, which you’ll see how to do shortly.

When performing sizing calculations, it is tempting to assume the nominal or average case for variables such as the number of rows. Consider calculating the worst case as well, as these sorts of predictions have a way of coming true in successful systems.

Calculating Size on Disk

In addition to calculating the size of a partition, it is also an excellent idea to estimate the amount of disk space that will be required for each table you plan to store in the cluster. In order to determine the size, use the following formula to determine the size St of a partition:

This is a bit more complex than the previous formula, but let’s break it down a bit at a time. Let’s take a look at the notation first:

-

In this formula, ck refers to partition key columns, cs to static columns, cr to regular columns, and cc to clustering columns.

-

The term tavg refers to the average number of bytes of metadata stored per cell, such as timestamps. It is typical to use an estimate of 8 bytes for this value.

-

You’ll recognize the number of rows Nr and number of values Nv from previous calculations.

-

The sizeOf() function refers to the size in bytes of the CQL data type of each referenced column.

The first term asks you to sum the size of the partition key columns.

For this example, the available_rooms_by_hotel_date table has a single

partition key column, the hotel_id, which is of type text. Assuming

that hotel identifiers are simple 5-character codes, you have a 5-byte

value, so the sum of the partition key column sizes is 5 bytes.

The second term asks you to sum the size of the static columns. This table has no static columns, so the size is 0 bytes.

The third term is the most involved, and for good reason—it is

calculating the size of the cells in the partition. Sum the size of the

clustering columns and regular columns. The two clustering columns are

the date, which is 4 bytes, and the room_number, which is a 2-byte

short integer, giving a sum of 6 bytes. There is only a single regular

column, the boolean is_available, which is 1 byte in size. Summing the

regular column size (1 byte) plus the clustering column size (6 bytes)

gives a total of 7 bytes. To finish up the term, multiply this value by

the number of rows (73,000), giving a result of 511,000 bytes (0.51 MB).

The fourth term is simply counting the metadata that that Cassandra stores for each cell. In the storage format used by Cassandra 3.0 and later, the amount of metadata for a given cell varies based on the type of data being stored, and whether or not custom timestamp or TTL values are specified for individual cells. For this table, reuse the number of values from the previous calculation (73,000) and multiply by 8, which gives 0.58 MB.

Adding these terms together, you get a final estimate:

This formula is an approximation of the actual size of a partition on disk, but is accurate enough to be quite useful. Remembering that the partition must be able to fit on a single node, it looks like the table design will not put a lot of strain on disk storage.

Cassandra’s storage engine was re-implemented for the 3.0 release, including a new format for SSTable files. The previous format stored a separate copy of the clustering columns as part of the record for each cell. The newer format eliminates this duplication, which reduces the size of stored data and simplifies the formula for computing that size.

Keep in mind also that this estimate only counts a single replica of data. You will need to multiply the value obtained here by the number of partitions and the number of replicas specified by the keyspace’s replication strategy in order to determine the total required total capacity for each table. This will come in handy when you plan your cluster.

Breaking Up Large Partitions

As discussed previously, the goal is to design tables that can provide the data you need with queries that touch a single partition, or failing that, the minimum possible number of partitions. However, as shown in the examples, it is quite possible to design wide partition-style tables that approach Cassandra’s built-in limits. Performing sizing analysis on tables may reveal partitions that are potentially too large, either in number of values, size on disk, or both.

The technique for splitting a large partition is straightforward: add an additional column to the partition key. In most cases, moving one of the existing columns into the partition key will be sufficient. Another option is to introduce an additional column to the table to act as a sharding key, but this requires additional application logic.

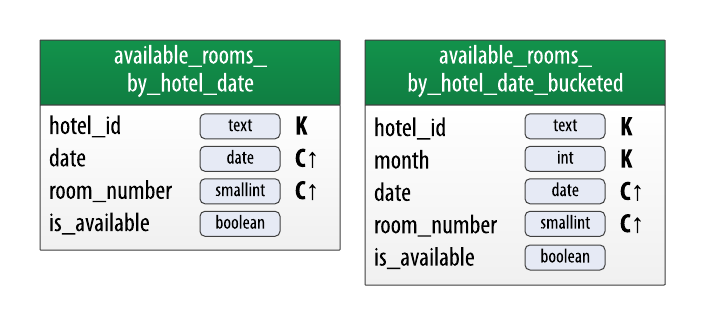

Continuing to examine the available rooms example, if you add the date

column to the partition key for the available_rooms_by_hotel_date

table, each partition would then represent the availability of rooms at

a specific hotel on a specific date. This will certainly yield

partitions that are significantly smaller, perhaps too small, as the

data for consecutive days will likely be on separate nodes.

Another technique known as bucketing is often used to break the data

into moderate-size partitions. For example, you could bucketize the

available_rooms_by_hotel_date table by adding a month column to the

partition key, perhaps represented as an integer. The comparision with

the original design is shown in the figure below. While the month

column is partially duplicative of the date, it provides a nice way of

grouping related data in a partition that will not get too large.

If you really felt strongly about preserving a wide partition design,

you could instead add the room_id to the partition key, so that each

partition would represent the availability of the room across all dates.

Because there was no query identified that involves searching

availability of a specific room, the first or second design approach is

most suitable to the application needs.

Material adapted from Cassandra, The Definitive Guide. Published by O’Reilly Media, Inc. Copyright © 2020 Jeff Carpenter, Eben Hewitt. All rights reserved. Used with permission.